Microsoft’s call for a Digital Geneva Convention (February 2017) – which should ‘commit governments to avoiding cyber-attacks that target the private sector or critical infrastructure or the use of hacking to steal intellectual property’ – attracted the attention of the digital policy community. It brought into focus the idea that, in the search for a more secure and stable Internet, Internet companies need to engage with governments and work together on reasonable policy arrangements. The proposal gave rise to many pertinent questions related to the future of digital governance, in particular in the security field. Here, we address some of them.

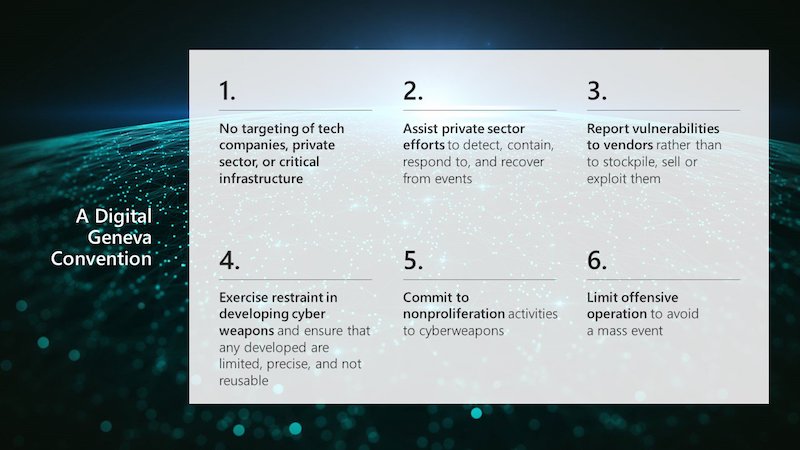

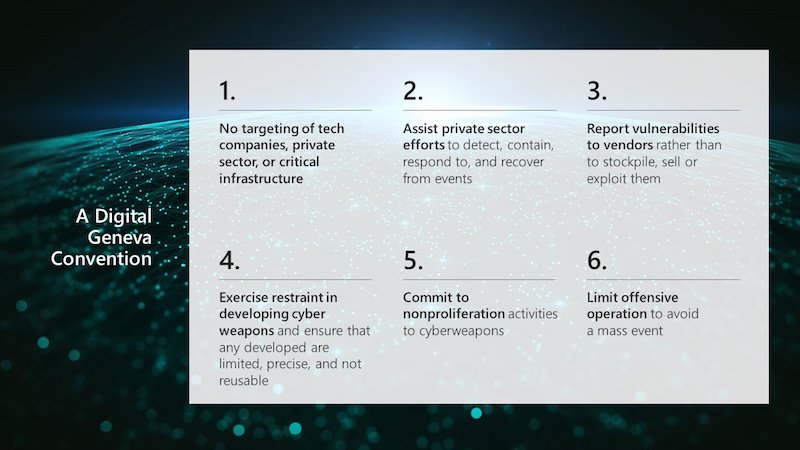

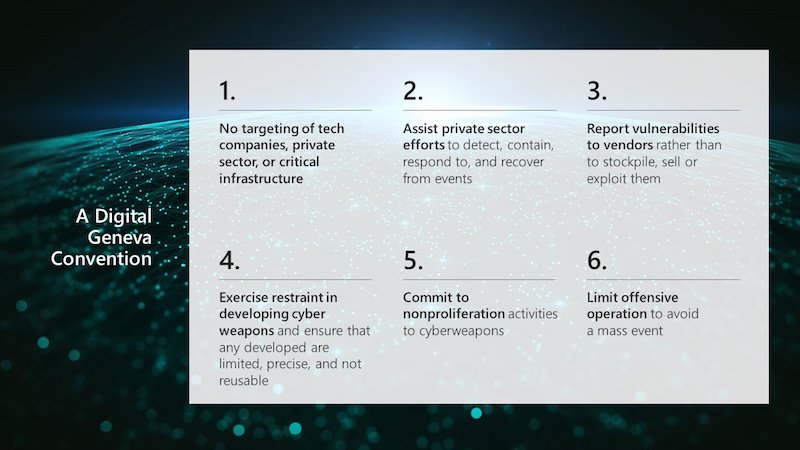

In April 2017, Microsoft’s Brad Smith announced three new documents that continue to shape the proposal for a Digital Geneva Convention. The first carries key clauses which should form part of the convention; the second outlines a common set of principles and behaviours for the tech sector to help protect civilians in cyberspace; the third proposes the setting up of an independent attribution organisation to identify wrongdoing. In May 2017, Smith renewed the call for a Digital Geneva Convention, in response to the WannaCry ransomware attack.

What is the main aim of a Geneva Digital Convention?

The Geneva Digital Convention, proposed by Brad Smith, Microsoft’s President and Chief Legal Officer, aims at creating binding rules out of the voluntary norms on secure cyberspace developed by the UN GGE and regional organisations. Embedded within a convention, these and few other additional norms could become a legal obligation, with the corresponding enforcement mechanisms. According to Microsoft’s proposal, the convention should motivate states to adhere to the agreed norms.

What should a Geneva Digital Convention regulate?

The six principles proposed by Microsoft are typically based in national security, related to both defensive and offensive cyber-operations. They are a mix of policy and legal regimes. Principle 1 could be classified as the ius ad bellum principle, dealing with justification and prevention of conflicts; principles 3, 4, and 5 have a strong cyber-disarmament focus; principles 2 and 6 are applicable both in conflict and peacetime operations.

Moving from the six principles, Microsoft’s arguments shift towards protecting citizens in the case of conflict – which in legal terms is known as ius in bello – or even broadly speaking towards what we might call human cybersecurity. Human security is anchored in the protection of human wellbeing. Since human wellbeing increasingly depends on digital space, the question of human cybersecurity is likely to come more into focus.

If Microsoft’s proposal aims to focus on human cybersecurity, this will bring developmental aspects into discussion – ensuring means for people to achieve cyber wellbeing (access to the Internet, development of local content, etc), as well as human rights issues, including a potential right to safe access to the Internet.

Image credit: Microsoft